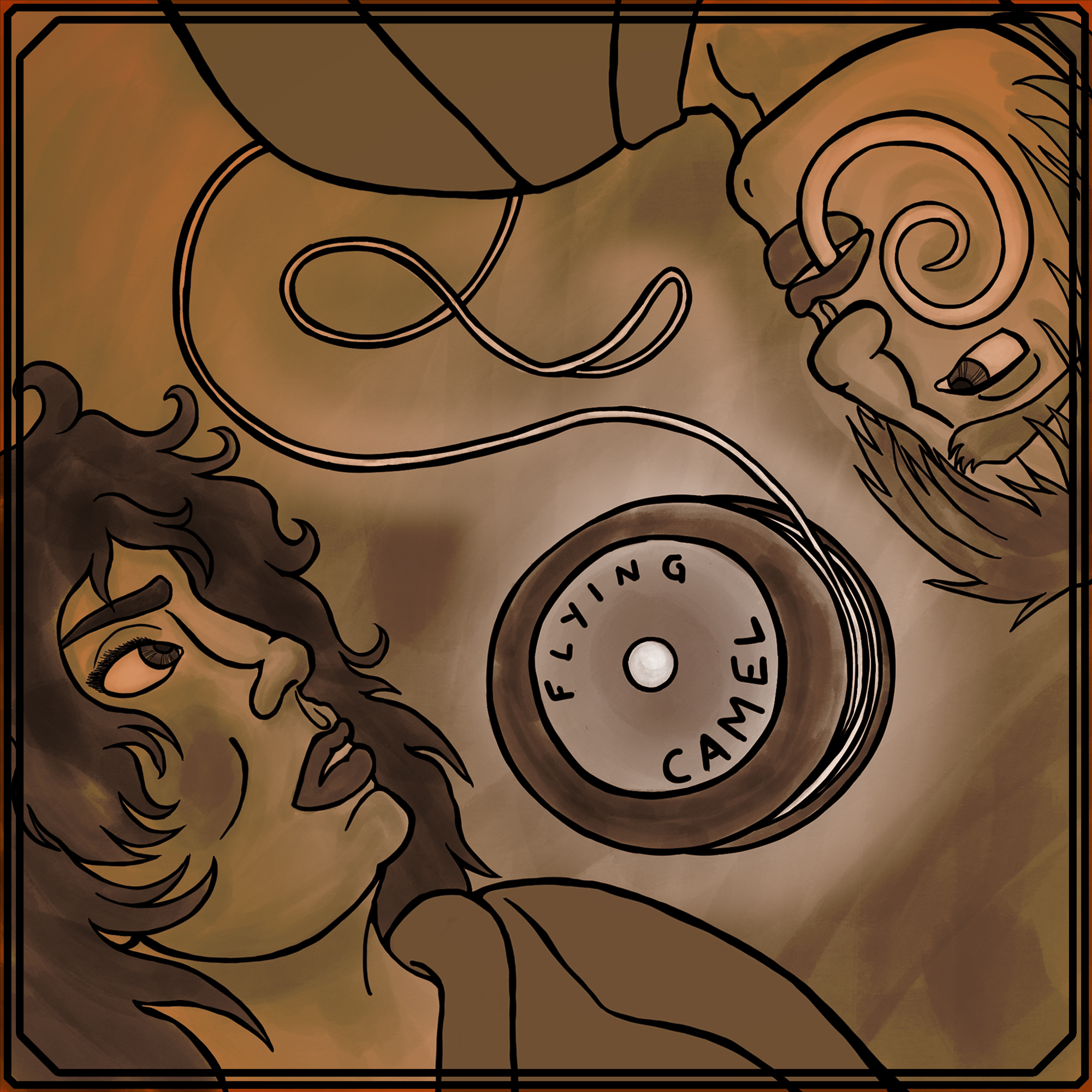

010: The Flying Camel Goes to Tigerwood, by Lisa M. Bradley

/About the Author: Forged in the scalding heat of South Texas, Lisa M. Bradley now lives in Iowa with her spouse, child, and two cats. More of her imaginings, always inflected by her Latina heritage, are forthcoming in PodCastle, Strange Horizons, and the Sunvault anthology. Her collection of short fiction and poetry is The Haunted Girl (Aqueduct Press). For more, follow her on Twitter (@cafenowhere) or visit her website: www.lisambradley.com

The Flying Camel Goes to Tigerwood

by Lisa M. Bradley

Up ahead, on the right side of the curving path, the dotted line went dark. A bit farther, a smeary mash of myco-luminescence, then the dots low to the ground resolved into regularity again. The mushrooms had been trampled.

Mireya paused, her shadow a hundred partial sketches cast by the mushrooms illuminating either side of the path. Her shadow appeared to tremble. She was not trembling, however. Not yet.

She squinted and made out a glowing smear on the grass, beginning near the smashed ‘shrooms and extending past the tree line. She lifted a hand to toggle off her music, but the implant behind her ear must’ve sensed her intent, for the sitar suddenly stopped. (Mireya couldn’t rightly afford the tech, but she couldn’t afford to live with Mother and not have it.) She redirected her hand to her jacket zipper and went dark.

Mireya doubted anyone was lying in wait. (Who’d want to rape a hippo like you, anyway? her mother sneered inside her head.) Probably dogs had torn up the lights, or drunken collegiates who’d stumbled off the path to splash in the creek. The creek bed was dry now, but the college kids would’ve missed that development during summer break.

Just in case, Mireya pulled the face flap up from her collar, pulled the hem down over her wide (scrumptious, she sometimes thought) hips. The jacket would do the rest, unspooling deflective shadows all the way to the ground and out a two-foot radius. Loose dogs or staggering drunks, she didn’t want to be seen.

Nobody ever sees you, her mother said. Even without that stupid cloak.

Mireya wondered why she was even going home. To watch Mother poke hair plugs into plastic doll heads while she belittled everything about Mireya but her size? But after a long day of kid wrangling, Mireya was tired, and no matter where she went, she’d still hear Mother’s voice. Each insult had been jammed into her head with the same brutal precision as the hair plugs in Mother’s piecework.

She continued up the path, attention darting side to side and up into the branches of the nearest trees. As she neared the bright burst of destroyed mushrooms, the scent of cedar grew strong. The mushrooms had been genetically tweaked to smell better: a bit of aesthetic engineering paired with the environmental.

Mireya’s view of the woods broadened. The glowing cream-of-mushroom tide beached at two large sneakers. She stared at the soles of a person lying belly-down beneath an oak.

Keep moving, dummy.

Had it been the voice of reason, Mireya might’ve kept walking. But it was her mother’s voice. So, with the feigned obliviousness that cushioned her ego and only infuriated Mother more, Mireya stepped off the path. Leaving luminescent shoeprints in the grass, she scanned the ground for a stick. But the area was well maintained, lest the mushrooms spread and turn the woods into a black-light poster. The only litter was spore-enriched mulch dragged from the garden beds and the chunks of smashed mushrooms.

She reached into her pocket, stopped within striking distance of the glowing sneakers. A young guy, she thought, studying the lean body on its belly, but she couldn’t be sure. Their jean cuffs were sodden with macerated fungus, the scent as sharp as the stains were bright.

Mireya pulled her Flying Camel out of her pocket, looped the string around her finger, and flicked the wooden yoyo at the body. She struck the back of one thigh—no response—and yanked the toy back. She did it again. And again.

On the fifth hit, her phone readied for speed-dial, she elicited a flinch. She pocketed her Flying Camel and said, “Eh, you a’right?”

The person gave a high-pitched whimper, much too small for their body, then struggled to crawl deeper into the woods.

“Should I call for help?” Mireya said, not following.

“What? No.” The voice, a boy’s, did not match the adult body. “He’s long gone.”

“Who is?” Mireya followed now, albeit tentatively. “Were you attacked?”

The person rolled over, panted, “Mostly mugged. Feels like he kicked me in the back of the thigh while I was out.”

Mireya cringed. “Sorry.”

“I’ll recover. Leave me.”

Mireya stopped. She didn’t know what to say. Mother, who was only speechless when Mireya’s music played, jumped in. See? Nothing for you to do here. Not sure why you thought you could help. Come home, cobweb head.

Mireya stepped forward. “I’ll help you back onto the path, if you think you can walk.”

“That might be a good idea,” he said, lurching into a sitting position. “Those maggots knocked me hard enough you’re a blur.”

“Oh!” Mireya stroked her zipper placket and went light again. “I forgot.”

“You too? The maggot that popped me was wearing a lightbreaker.” He brushed dirt from his hair and face with a chuckle too high-pitched for the bitterness of his words. Must’ve been using a vo-synth. “At least I’m not seeing skewed. Full up on problems as it is. Don’t need to add brain trauma.”

“Why don’t we go to the bridge? I can look at you under the lamps.” Mireya pocketed her phone and offered him a hand. “I’ve got a first-aid kit in my bag.”

“You a medic?”

She pulled him to his feet. Face to face, she saw his tusks and understood why he used a vo-synth, though not why he’d chosen a child’s voice. The tusks extended from his upper jaw, above the canines, down past his bottom lip, where they curled around the corners of his mouth and up to either side of his round nose. From there, they curved out to follow the lines of his cheekbones. The bones, about as wide as a toothbrush, were spiraled. Mireya liked tusks, but enough people didn’t that he may have been discomfited by her gaze.

“Are you a medic?” he demanded.

The vo-synth rendered the imperious question charming. Thinking of her more precocious charges, Mireya smiled and said, “No, I’m an elementary teacher. But sometimes it’s the same thing.”

“I’ve got to go.” He shook off her hand. “I think I know where he’s heading.”

“You’re going after the trog who popped you?” She followed as he limped into the woods, presumably cutting across to the other stone bridge that spanned the empty creek. “That’s not wise. You lost consciousness, you could have a concussion.”

He turned to scowl at her. “What are you doing?” Moonlight stuttered off the spiral of his right tusk. His childish pique didn’t diminish the menace, but his long eyelashes and reddening cheeks did.

“I’m going with you,” Mireya said, slightly breathless. Not from keeping pace—he was wobbling rather than running, favoring the yoyo-struck thigh—but from forcing her assistance on him. It was rare she overruled anyone over five feet tall.

Plus, Mother’s voice was in her head again, chiding her for meddling, for talking to strangers, for roaming the woods with a man she didn’t know. Mireya tried not to speak louder to compensate for the running critique no one else could hear. “If you fall and crack your skull in the woods,” she said, “or those muggers kick the fluff out of you again, I’d feel terrible, knowing I didn’t do anything to stop you.”

“Don’t you have anything better to do? Mixing yourself up in stranger’s business…” His disdain trailed off. He sprinted away. Evidently he’d chosen to save his breath for outrunning her.

Mother did not have to breathe to rebuke. Aren’t you ashamed of yourself, chasing after this man? Leaving me to wonder and worry at home?

“Not really,” Mireya chirped, and ran after him.

A wrench in their routine might be exactly what Mother needed. She could soliloquize before an audience of wide-eyed doll heads, all of whom, in their variously remedied stages of baldness, were better listeners than Mireya with her implant.

Besides, it wasn’t every blue moon that Mireya met a tusked boy in the park. An extended conversation with a cute one? Even rarer than a pink katydid.

More like a flying camel.

•••

They exited the woods half a block from the stone bridge Mireya had been thinking of. They vaulted down a small hill and out of the park. Limping, he charged across the cracked asphalt and defunct streetcar tracks, not looking either way. Mireya paused on the crumbling curb out of habit. A tuk-tuk puttered north, its headlights quivering at every bump in the road. Mireya judged she could outrun the auto-rickshaw and scurried across.

“Wait for me! How do you know where the mugger’s going?” she asked.

“He’s going where I was,” he called over his shoulder.

“You know him?”

“Not by name,” he said, peeved.

They passed a panadería shuttered for the night. Vanilla, molasses, and toasted pecan scents followed them to the iron-gated phone store, then ceded to the nose-prickling chemical stench of a dry cleaners. As in Mireya’s neighborhood, the surveillance cameras and drone docks had been fragged, but the solar lamps glowed softly. When they rounded the corner, where a bike library operated, the guy seemed to accept he couldn’t shake Mireya.

“I was carrying moss balm. For Tigerwood, the complex where I live,” he panted. “This guy’s probably going to dump it in a drain in or near the building, so it will clog up the sewers.”

“Why?”

“So the owner can evict us for using an unlicensed remediation matrix. Which we are, or would, or will, but only because he refuses to repair anything. Plans to sack us for a glitzy new biz pavilion.”

His sneakers pounded the buckled sidewalk and hers clomped over the iridescent smudges he left in his wake. She asked no more until Tigerwood came into view.

From the name, she supposed the exterior had once been topaz or amber, but now the peeling bark was a sickly chartreuse. A crowd argued in front of the portico. If Mireya squinted, she could imagine the knobby texture of an acorn cupule for the roof, but currently the portico was as worn as a sunken stone quay. The watery blue light rippling from its lanterns cinched the resemblance.

“How can anyone doubt it’s dying?” she said, gaze tracing decay. Beams pulled from the cylindrical building like dried-out sunflowers. Wires poked from the threadbare façade.

“Owner says Tigerwood’s repairing itself. Slowly. We need to be patient,” he sneered. He slowed to a walk and smoothed back his sweaty hair, rubbed the back of a hand over each eye to clear sweat from his brow. He reined in his limp.

“But if there were any improvement, wouldn’t you know?”

“He’s a Tuskeptic. Doesn’t believe our tusks can detect chemicals in our environment. Pretty convenient, eh?”

Mireya quashed her instinct to say, “But every scientific organization in the world accepts that human tusks function as sense organs!” This was not the time for “everyone knows” naivety. And then, among a clutch of children in the crowd, Mireya recognized a student, Lucille. She hadn’t realized the girl with beads in her braids might be a Tusk-child. Of course, tusks didn’t appear until puberty and this child was a first-grader.

“Miss Mireya!” Lucille yelled with joyous surprise. “What are you doing here? I never knew you knew Coterie!”

Lucille broke from the cluster of kids, some of whom wore the near-infrared LED visors that Mireya’s school hated. The LEDs blocked facial recognition programs on most surveillance cams. Lucille ran over and shook Mireya’s hand hard enough to swing her whole arm.

“Careful, you’ll yank it off,” Mireya teased.

The tenants were facing down three men. The first, angular as bent rebar, wore street clothes, including a dirty jacket (which might’ve been a lightbreaker) tied around his narrow waist. His sneakers glowed a giveaway as clear as the twitch he couldn’t hide when Coterie joined the tenants’ ranks. The other two men strained believability and the boxy lines of their maintenance uniforms with copious muscles. One gripped a toolbox. The horseshoe of angry tenants included people with tusks and without. Some elders were “mix-skins,” their skin quilted-looking from the grafting techniques used back during the necrotizing fasciitis epidemic. Tenants of all ages wore sousveillance lanyards and jewelry, trusting their own tech more than street cams or drones to record the détente outside Tigerwood.

A black man holding a Chihuahua gave Coterie a synopsis of what he’d missed. Thanks to Granny, a stout woman whose bald head shone in the portico light, the three men hadn’t gotten farther than the first-floor foyer. At her alarm, the tenants had flooded out of their apartments to expel the intruders.

“We’re not intruders,” the man with the toolbox said. “We’re maintenance! We’re just here to replace the couplers in the filtration system.”

“That’s right,” said the other uniformed man. “Haven’t you people been purple-faced ‘bout how long it takes to get repairs? And now you’re stonewalling?”

“You don’t have names on your uniforms,” said the man with the Chihuahua. Mireya guessed he’d been walking his dog earlier; the Chihuahua sported a quilted vest with reflective trim.

“Or photo ID on your key cards,” said a woman with dreads and librarian spectacles. She stood on the top step of the portico, not looking at the men but at the holo spooling from the sousveillance bauble on her necklace.

“And who’s this guy?” Coterie said, pointing at the man in glowing sneakers. “Independent contractor?”

“What’s that? I don’t understand babytalk,” said Toolbox Man. “Leave this to the grownups, will ya, kid?”

Coterie snorted. “Why don’t you leave this to folks with two brain cells to rub together?”

Mireya nudged Lucille, whispering, “Go back to your parents.”

Granny spoke up. “Ya les dijimos, if you’re maintenance, then call Mr. Mash and prove it. Let him verify you and your purpose here.”

The second uniformed man gave a gusty sigh. “And I told you, ma’am, Mr. Marshall’s left the office by now.”

“¿Usted no tiene su número personal? Dime otra,” Granny said. “You just don’t want a trail leading back to him!”

Mireya took a few steps back. “Looks like you’ve got your hands full, Coterie. I’ll see you later.”

Coterie’s lips pulled back. Not a snarl, exactly; maybe a moue of annoyance at her feigned familiarity. Though that smarted—was it so implausible that they could be friends?—Mireya slowly backpedaled.

“If you can’t provide credentials,” the Dread Librarian said, reclaiming the maintenance men’s attention, “then perhaps my friend at the Town Crier can dig ‘em up.”

At mention of the newspaper, Mireya may as well have dropped into a vacuum. The supposed maintenance men shouted and charged forward. En masse, the children were swept behind adults. The only tenant who saw Mireya touch her zipper placket was the Chihuahua, which reared up in its person’s arms and thus got juggled into a “burp the baby” position.

While the uniformed men swiped at the cameras leveled at them, Mireya took out her Flying Camel. A couple of quick throw downs to test her string… She positioned herself a few feet behind the mugger. The Chihuahua wriggled around to bark at her, but no one paid attention to its yapping, too embroiled in the maelstrom of jeers and counterjeers.

Mireya launched a forward pass that smacked Coterie’s mugger in the hip. He cursed and turned in time to get a modified moon shot to the face. He clapped his hands over his suddenly spurting nose and Mireya sidestepped the blood flow. The empty-handed Uniform Man turned to stare at the mugger in bafflement. Toolbox Guy trailed off mid-rant, unsure what was happening.

The tenants didn’t look any surer—except for the Chihuahua—but Coterie advanced on Toolbox Guy. Mireya, knowing Coterie’s hidden injuries, felt a rasp of panic until she noticed two tenants following his lead.

She focused on Uniform Man again. She pinged his funny bone with a forward pass, then dropped into a squat.

“Hey!” Whirling, holding his injured elbow, he glared at the air above her head. She hammered his kneecaps with four rapid-fire breakaways before he stumbled forward, one hand groping for the yoyo. Mireya fell on her butt and rolled to the side. She accidentally kicked Toolbox Guy, giving the tenants the advantage. Coterie ripped the toolbox from his hand.

The mugger took one hand from his face long enough to untie his jacket. Hunched against further blows, he struggled into his jacket, went dark, and ran. The Chihuahua erupted from its owner’s arms. Ignoring the man’s cries, the dog bolted after the shadow that kicked up pebbles and grit.

Mireya rolled clear of the ruckus. A fatherly Tusk and a teenager restrained Toolbox Guy while Coterie fought the latches on the box. Mireya checked on Uniform Man and saw the Dread Librarian struggling to hold him off, until a woman with one broken tusk, dressed like a bank teller, appeared to help her.

“Hot cha!” squeaked Coterie. He brandished a vial that Mireya presumed held moss balm.

“Here, boy,” called Granny, and he tossed it to her. The tenants parted for her to hustle up the portico and inside Tigerwood. Once she was out of sight, the two tenants released Toolbox Guy. Uniform Man raised his arms in surrender, and the Dread Librarian and Bank Teller eased off.

“Congratulations,” spat Uniform Man. “You just blitzed the ones came here to help you. See if the boss ever bothers with you freaks again.”

“Take your exhaust elsewhere,” the Dread Librarian said.

Now both empty handed, the uniformed men staggered away. The tenants watched until they were halfway down the block, then adjusted their sousveillance devices, deleting evidence of the physical altercation. No matter how justified, any attempt at self-defense got “freaks” like them labeled antisocial, inherently violent, so no use saving that data. If only reality were so easily edited, Mireya thought. She might not’ve needed her implant to stave off Mother’s voice.

She heaved herself to her feet and brushed off her (scrumptious) aching bum before going light. Lucille swung off the portico and pounced on her in celebration.

“Miss Mireya, that was not schoolish at all,” the girl crowed. “And I’m so glad!”

“Me too,” Mireya said, smiling as she tucked her yoyo away.

“Yeah, most like, you’re feeling quite heroic,” Coterie sneered.

Clicking came from around the corner. The Chihuahua returned with a glow-in-the-dark grin. Its owner screeched with joy before remembering to scold the animal for running off “all vigilante style.”

“Coterie,” said the fatherly-looking tenant. “Whatever the girl’s motivations, she did us a good turn. Respect that.”

“Davíd, I don’t even know who she is,” Coterie said, blushing under the admonition. “I haven’t been able to scrape her off since the park. Really, lady.” Coterie turned to Mireya. “Who are you? What do you want?”

“She’s Miss Mireya,” Lucille said, sounding exasperated. “She’s a teacher at my school. Second grade, right?”

Mireya nodded. She hoped her teary eyes weren’t obvious in the aquatic light. She’d hit pavement during the fight, but it was Coterie’s disdain, so in line with her mother’s, that really hurt.

“I’d like to see the moss balm at work,” she told Davíd. “If that’s not too much imposition. I won’t tell anyone, I promise. I’ve just never seen a remediation.” For as long as she could remember, she’d lived and worked in dead-tech buildings, hollow as her mother’s doll heads. Every last one had been intended as a temporary structure, but all had been pressed into long-term, even permanent service.

“I’ll go ask Granny,” Lucille announced, darting from Mireya’s side.

Coterie sighed, but Davíd laughed. “If Lucille asks, it’s as good as given,” he said. “Come, let’s go inside.”

•••

Wordlessly they descended the dimly lit, spiral staircase. It made Mireya think of tusks. Davíd led the way, and Coterie followed Mireya. She was very aware that she was panting, both from the panic of the fight and the exertion of the stairs. She wondered if she smelled bad. She couldn’t smell herself, but she was sweaty. The whisking of her jeaned thighs rubbing together seemed deafening, but nobody called her a hippo.

In fact, Mother’s voice had been silent for many minutes now. Not drowned out by chaos, as it often was when Mireya was surrounded by students—although that was its own, welcome relief. This was a peaceful reprieve, akin to when she toggled her implant.

Lucille’s laughter beckoned. A flickering orange light, as if they were sinking into a cool bonfire, waited at the base of the stairs. Mireya smelled earth, but also grease and friction. The spiral staircase wound around an elevator shaft. If Tigerwood were an actual tree, then the elevator shaft would be its trunk. Above, she thought, each cylindrical floor must be divided into wedges for rooms.

A cluster of curious children surrounded Granny, who used a paintbrush to apply a mossy shake to Tigerwood’s heartroot. The heartroot spanned the back of the elevator shaft, thick as one would expect for a major artery. Flaked-off bark fanned the soil around it. Mireya stepped away from the staircase so Coterie could get past her bulk, but she moved no closer, not wanting to burst the bubble of intimacy.

“It’s just water and the moss balm?” asked a child in a sweatshirt and tutu.

“Has to be Tigerwood’s water, run through the cycle at least once,” Granny said, head tilted, as if listening to the root. “Mas es mejor.”

“Won’t the city know we used it without p’mission?” asked an older child, looking worried.

“No te preocupes, queridos. Tigerwood’s sad sick and this will help only a little. Besides, Mr. Mash won’t complain to the city. He doesn’t want to draw attention to how bad he’s let things get.”

Watching Granny’s brush strokes reminded Mireya… When she was eight, she’d had a fever and headache, and Mother had held her head in her lap and rubbed from her forehead to her temples, temples to jaw, jaw to neck, and then all the way up in reverse. All in silence. Mireya had felt as if tendrils of power were spreading from her mother’s fingers and into her skin, through her rigid muscles, under her hotpot skull to rub the ill away. She’d not have edited that memory for anything.

More scales of bark drifted to the floor as Granny finished. She squeezed the wet bristles and wiped the residue on a bare spot of heartroot. Then she ran her fingers along the inside of the jar to collect the dregs and anointed a different spot, as if allowing Tigerwood to lick the spoon.

“Seen enough?” Coterie said, turning to Mireya.

“Yes.” She nodded gratitude at Granny. “Thank you for letting me come into your home, to see this.”

Granny nodded, and Davíd said, “Thank you for helping us out there. You didn’t have to get involved.”

Coterie clapped his hands loud enough that Lucille squealed. “Dinner time,” he announced. “Get upstairs to your rooms! Aren’t you hungry? Don’t you have homework?”

He stomped at the children, as if to chase them upstairs, but Granny said, “Coterie, I know you’re going to walk this young woman home.”

Despite her warning tone, Coterie scoffed. “Granny, she doesn’t need me. You saw! She’s self-reliant.”

“Bona fide!” Lucille said, draping herself along the banister. “Show us some yoyo tricks, Miss Mireya.”

Davíd shook his head and lifted the child in the tutu. “No more tricks tonight. Miss Mireya needs to get home and you need to nourish yourselves before bath and bed.”

Granny, hand to heartroot, said, “Coterie, where is the gentleman who opens every door for me? Who always walks me to church, even if he’s too endeviled to stay for mass?”

Mireya enjoyed Coterie’s blush, the way his lowered lashes underscored the crests of his cheeks. She even liked how his lips crimped around his tusks to keep from protesting. Used to her mother’s criticism, she didn’t take Coterie’s petulance personally. But evidently Granny did.

“Don’t shame me, boy. Miss Mireya was good to Tigerwood. You pay Tigerwood’s dues, you might even get a goodnight kiss from the deal.”

Coterie’s eyes bulged, his cheeks blazing. “Granny!”

•••

In the park again, Coterie trudging by her side, Mireya tried to imagine Mother’s face when she’d walk up to their dead-tech, brick-and-mortar apartment building, escorted by a man. She couldn’t. Such a thing had never happened before.

Coterie, who’d slouched back into a limp as they left Tigerwood, mumbled in his high-pitched voice. “…walk the dog…”

Granny’s power must’ve worked a balm on Mireya’s esteem, for she felt insulted enough to snap, “What was that?”

Surprised, Coterie straightened and blinked at her. Owlishly, she thought, but moonlight darted off his tusks again, mixing the metaphor. “I said, can you do that trick, walk the dog?”

“Oh!” This time, Mireya blushed. She wondered how many come hithers she’d missed over the years, her hearing occluded by music and Mother. “Yes. I can teach you, if you like.”

Coterie shrugged as if he didn’t care, but Mireya sensed another pink-katydid, flying-camel opportunity. She got out her yoyo. Its polished wood surface felt crusty, so she scraped it against her jeans.

“Your jaw reminds me of ‘America, the Beautiful,’” she teased. When he rumpled his brow quizzically, she elaborated. “Purple mountains majesty?”

Rumple turned to scowl, so rather than comment on the bloody cut near his hairline, Mireya said, “Once we get near the bridge, where the sidewalk flattens out, I’ll show you some tricks.”

“Lucille will be jealous,” he said, easing again into his pained slouch.

They hadn’t gone more than five steps before the quiet squeezed Mireya. “Can I ask you a question?” she asked.

Coterie’s arched eyebrow implied, Can I stop you?

“Why did you choose that voice? For your vo-synth?”

“I didn’t choose it. It’s mine. We harvested the phonemes before my tusks extended.”

“Before they impeded your speech,” Mireya said, so he knew she wasn’t completely ignorant. “But, well, it causes problems, doesn’t it? The way Toolbox Guy insulted you?”

Coterie shook his head. “Trogs like that? They insult regardless. You imagine boar boy or walrus were far behind? I’d rather sound like a kid than a stranger.”

Though startled by the epithets, Mireya nodded, slowly processing. “I guess saying ‘Change your voice’ is like someone telling me ‘Lose weight and your mother will stop calling you hippo.’ But she’d just switch to something else.”

“She calls you that?” At Mireya’s nod, Coterie shook his head. “That’s cutting.”

Mother’s voice surfaced long enough to stutter outrage but, given the garbled syllables, Mireya easily squelched it. “She’s no Granny,” Mireya admitted. “Speaking of, you don’t have to worry. I don’t expect a goodnight kiss.”

“That.” He sighed and peered up past tree branches. “It’s nothing personal, promise. It’s just, have you ever kissed a Tusk before?”

Mother reared up again, but Mireya wouldnotwouldnotwouldNOT admit how few people she had kissed, ever. Staring at the toes of her shoes, she focused on releasing one syllable. “No.”

“It’s always awkward the first time.”

Always. Mireya smiled. She and Coterie were on opposite sides of that spectrum. To her relief, the ground around them went light. The faint myco-illumination at their feet gave way to the overlapping spotlights of solar lamps. They were nearing the bridge.

Mireya readied her yoyo for a simple throw down. By the solar lamps she saw the crust still marring its smooth wooden surface: dried blood. She stopped walking.

“Here.” Coterie stopped, too, and reached for the yoyo.

Mireya demurred. “No, I don’t think you want to—”

“Trust the tusks,” he said, coming closer. “I’m not going to catch his bladder infection, and that’s the worst he’s got. I’d smell it in his blood.”

Mireya hurried to unhook the string from her middle finger but, panicked at his proximity, she only tangled it. Coterie took her wrist and unraveled the knot before slipping the string off. She watched, feeling the transferred heat of his touch dwindle as he bundled the yoyo in his shirt hem and roughed it clean.

“Thanks,” she murmured.

A moment later, he held out the toy. She tried to take it, but he held tight until she met his eye.

“I’m sorry I was rude before,” he said. “I get angry about Tigerwood.”

Mireya nodded. She took the yoyo and danced away from Coterie and the serious moment. “Prepare to be wowed.”

“Already am,” Coterie said, smiling. The tusks gave it a roguish quality.

You ditched me so you could bore a man to death? Mother snapped. Stop mooning over him and do something!

For once, Mireya obeyed her internal Mother. Forget walk the dog. Coterie’s first smile deserved better, a special trick, with a name silly enough to keep him smiling. Heart pounding, Mireya rolled up her sleeves.

“Kind sir,” she said. “I present to you, Boingy Boing!”

End.